India is already one of the most water stressed countries in the world.

↓ Scroll to continue

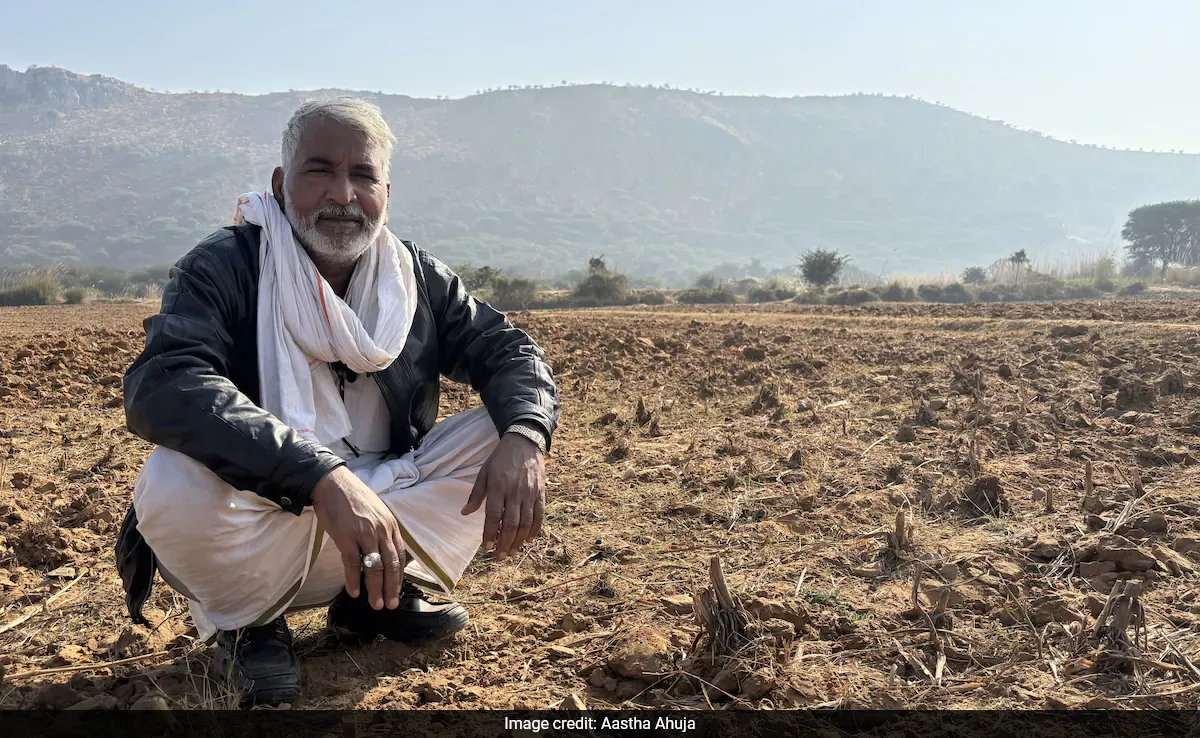

Cash cropping, free electricity to pump groundwater and overuse of chemicals have left the soil dead and dry.

According to future projections for 2030, 2050 and 2080, unless India dramatically changes the way it uses water to feed its people and the world, things are only going to get worse.

Deeper and Deeper: India’s Water Race to the Bottom

Over-exploitation of India’s groundwater for thirsty cash crops is threatening water supplies, leaching the soil and endangering the food security of all Indians, a Thibi data investigation reveals.

5 Jun 2025

India is draining dry its vast supply of groundwater fast.

In 2023, India pumped around 241 billion cubic meters of groundwater – more than the United States and China together used. Three in every 20 groundwater blocks slipped into critical or over-exploited condition, where water is being withdrawn faster than rain and surface water can replenish it, leaving no groundwater for next year.

Agriculture remains the dominant driver. Nine out of every 10 liters of groundwater extracted were used to irrigate fields, pushing reserves to the brink.

Farmers across India are drilling deeper wells in a desperate bid to find water – some reaching depths of over 1,000 feet, roughly as high as the Eiffel Tower.

India has over 1.4 billion mouths to feed, yet a major investigation by Thibi and media partners across India reveals that pursuit of profits, not food security, have precipitated the current crisis.

Fourteen journalists from eight states and union territories embarked on a six-month investigation into India’s groundwater crisis, interviewing more than 150 experts, farmers and policy makers and compiling over 50 datasets on water, crops, trade, soil, nutrition and food.

This cross-border investigation reveals how India has squandered a valuable resource and in many places, has caused irreversible damage to people and the environment. Large scale intensive farming of thirsty cash crops catalysed by government policies that encourage instead of controlling irresponsible water use have already had wide-ranging consequences for the land, the farmers who depend on it and the people who have no choice but to consume less nutritious foods than previous generations.

How Cash Crops are Sucking India Dry

A government push in the 1960s, known as the Green Revolution, fundamentally transformed India’s agriculture, forcing farmers to stop growing diverse, healthy, sustainable crops such as sorghum and millet to growing industrial-scale thirsty cash crops, the fallout of which we can see today.

In nearly 80% of Indian states, just five crops have dominated farmlands over the last decade. While the crop mix varies from state to state, rice or wheat – sometimes both – consistently make the list.

Together, the top five crops take up a large share of the country’s cultivable land – often at the cost of long-term water sustainability.

These staples are among the thirstiest: growing one kilogram of wheat in India, on average, requires over 1,100 litres of groundwater, while paddy needs 452 litres per kilo. To put that into perspective, if you take the water used to grow one kilogram of wheat and instead use it to grow other crops, it could produce enough rice to feed 25 people or millets to feed more than 150 – compared to just 10 people with wheat, assuming a 100-gram serving per person.

This is the reality of monoculture in India and what it has done to the water supply.

1

2

3

4

5

The Environmental and Nutritional Cost of Water Thirsty Crops from Water Stressed Farms

The investigation confirms the irreversible damage of intensive farming that farmers have long suspected.

Farmers drill deeper to reach more water.

They flood their fields to satisfy water-thirsty crops.

The water leaches the soil of essential nutrients.

Farmers dump large quantities of chemical fertilisers and pesticides on their fields to attempt to offset the damage.

The fields produce less nutritious foods because of the depleted soil.

People consume this food, unaware that the food on their plate is less healthy than it used to be.

Analysis suggests that crop diversity and soil health are linked. Monocropping of water-intensive crops is degrading Indian soils by reducing microbial diversity, increasing salinity and stripping the earth of essential nutrients.

In Punjab and Haryana, where fields are mostly dominated by rice, wheat and a few other crops, soil tests showed higher levels of salinity and the lowest levels of organic carbon, which helps the soil retain water and nutrients.

More than a third of Punjab’s samples tested by the government lack basic macronutrients nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Low soil nitrogen, for instance, hampers protein synthesis, leading to rice with reduced nutritional value.

Even in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Meghalaya and Tamil Nadu, states with relatively higher diversity, over a third of soil samples lack key micronutrients iron, sulphur and zinc, and it could ripple through the food chain. Iron-deficient soils yield grains low in iron; zinc-deficient soils produce zinc-poor cereals; while low sulphur diminishes the protein quality of pulses and oilseeds.

This erosion of soil health fuels a dangerous cycle: unhealthy soils produce less nutritious crops, which, in turn, could contribute to malnutrition and anaemia. To compensate, farmers rely more heavily on fertilisers but soil scientists warn that excessive use of chemicals could reduce yield and threaten food security in the long term.

This is how soil degradation and its health consequences play out across the country.

1

2

3

4

The Big Business Behind Big Farming

India’s most lucrative crops are not just water-hungry, but they are also shielded by powerful interests who exploit India’s lack of regulation over water use to get rich off of the virtual water trade. As global demand and export profits surge, so does the cultivation of high-value crops. In regions like those in Maharashtra, where the sugar industry is tightly woven into local politics, the entire system – from farms to mills – operates with little scrutiny. Groundwater keeps declining yet no meaningful reform is on the table as those who profit most are often the ones in power.

Basmati rice sits at the heart of India’s agricultural export boom. The country supplies three out of every four kilos of basmati rice consumed globally. Between 2013 and 2023, it exported 135.8 billion kilograms of rice, earning an estimated $82.8 billion. Basmati made up a third of that volume, but half the revenue.

Much of it comes from Punjab, where nearly every district is running dry. In 2023, top Basmati producers Amritsar, Tarn Taran, and Sangrur pumped out more groundwater than they had to spare – with Sangrur draining three years’ worth of supply in just one, Tarn Taran more than double, and Amritsar not far behind.

Like basmati, cotton and sugarcane are major exports and highly water-intensive. Their cultivation has surged in states such as Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, where groundwater is increasingly under strain, indirectly exporting its most valuable resource: water.

Yet nowhere is the grip of political interests more apparent than in the sugar industry in Maharashtra. The burden falls the hardest on farmers and labourers – those at the bottom of the chain – who face delayed payments, mounting debt, and, for those on the wrong side of power, fields full of unsold produce.

Across the country, big business interests drive some of the most reckless water use.

1

2

The Government’s Role in Pushing India to the Brink

India has made public commitments to embrace sustainable agriculture – promoting millets as a climate-resilient grain, running water conservation campaigns and promising to modernise farming practices. But in the data and on the ground, much of it rings hollow. Government policy continues to prop up the very system it claims to reform.

Researchers suggest that the Minimum Support Price – the government-set price at which it purchases crops from farmers – and other subsidies may have led to a 30% overproduction of water-intensive crops. And on the other extreme, the government does not procure more water efficient crops, like millet, that could reverse environmental damage and provide more nutritious meals to millions of Indians. Instead, it continues to buy more water-intensive crops like wheat and sugar.

Electricity subsidies, meanwhile, enable virtually unlimited groundwater withdrawals. Cheap, unlimited power encourages indiscriminate pumping and flooding of fields, even in districts already flagged as water-stressed.

In Haryana, for instance, the share of farms irrigated by tubewells climbed from half to two-thirds in just two decades.

This policy also inadvertently discourages the adoption of more efficient irrigation methods. Micro-irrigation, a more sustainable alternative, is used on just one in nine hectares of farmland nationwide. In Andhra Pradesh, where coverage is higher than the national average, improved access to water has ironically led farmers to grow water-thirsty crops, deepening the crisis rather than easing it.

But for farmers who wish to move away from monocropping by switching to organic farming or planting local varieties, the state offers little support, making it a financial gamble.

In the end, the system rewards those who plant high-yielding, water-thirsty cash crops and punishes those who try to break free.

1

2

Methodology

Credits

Reporting for the stories were supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy, a programme of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

Fellows\ Aastha Ahuja, Aishwarya Mohanty, Akash Chandrashekhar Gulankar, Amitha H Balachandra, Anant Prakash, Anupama Chandrasekaran, Arathi M R, Ashwini Kumar Shukla, Madiha Khanam, Navya P K, Nitesh Kumar, Utkarsh Tripathi, Varsha Singh, Vandana K

Story Mentors\ Supriya Vohra, Nihar Gokhale, Thin Lei Win, Sweta Daga

Data Mentors\ Aika Rey, Lu Min Lwin, Surbhi Bhatia, Kavya Sukumar, Thi Ha Ko Ko

Editor\ Eva Constantaras

Project Managers\ Sweta Daga, Paul Nicholas Soriano

Code & Design\ Elvin Oo, Thin Thinzar Htet, Zin Min Htut Oo

Interactive microsite developed by Thibi